January 6 vs. Historical Insurrections: A New Low?

By News & Trade Insights Team | Politics, History, Trade Tariffs

Introduction: What January 6th Means in American History

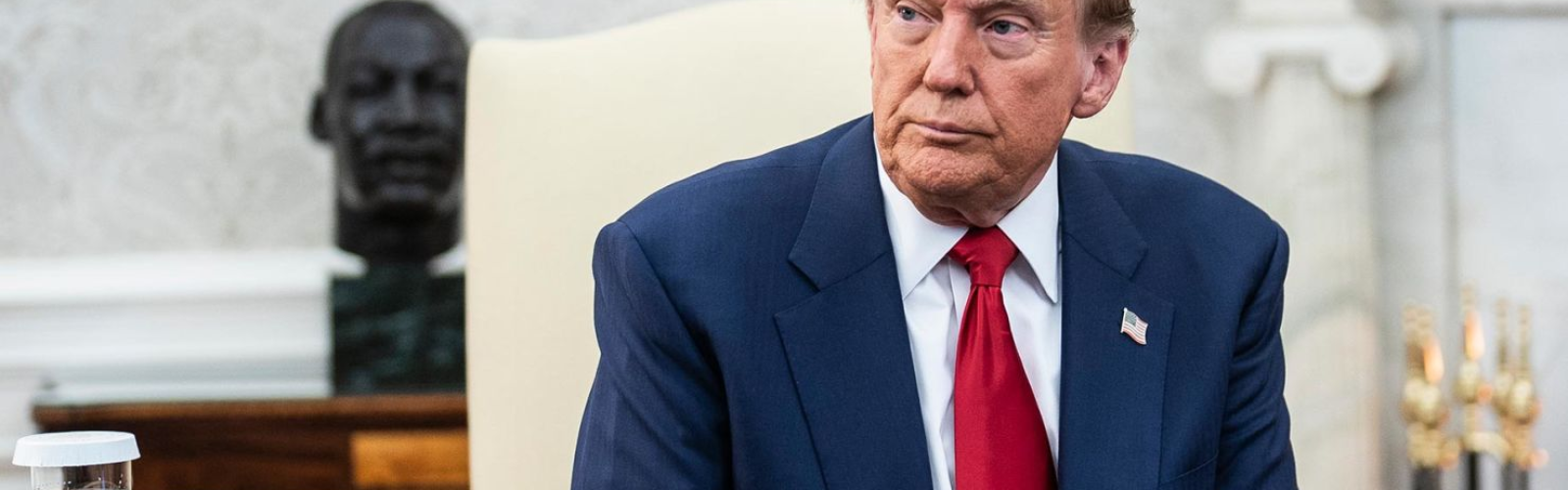

January 6, 2021 shattered the sense of democratic continuity in America. The storming of the U.S. Capitol by supporters of then-President Donald Trump shocked citizens, lawmakers, and the international community. As lawmakers were certifying the results of the 2020 Presidential Election, rioters breached security, vandalized government property, engaged in violence against law enforcement, and called for the overturning of a legitimate electoral process. The events triggered a nationwide debate: Was this a tragic but isolated event, or does it stand among the darkest chapters of American—and global—insurrectionist history?

As a news, politics, and trade policy platform, it’s essential to analyze January 6 in context. By comparing it with other historical insurrections, both at home and abroad, we can better understand where this event fits in the broader scope of political violence, the rule of law, and the stability—or vulnerability—of democracy. Is January 6 a new low, or a replay of earlier unrest? Let’s dive deep into the history and consequences.

Main Research: Historic Insurrections and the Uniqueness of January 6

A Brief History of Insurrection in the United States

The American Republic has weathered numerous internal threats, from the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, to John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, the Civil War (1861–1865), and violent labor uprisings like the Haymarket Affair. Each of these uprisings challenged the federal authority but varied in intent, violence, and outcomes.

- The Whiskey Rebellion (1794): Triggered by a federal excise tax on whiskey, Western Pennsylvania farmers violently resisted tax collectors. President George Washington personally led militia forces to suppress the revolt—demonstrating federal authority.

- John Brown’s Raid (1859): The abolitionist’s attempt to spark a slave uprising by seizing the federal armory at Harpers Ferry ultimately failed, but it fanned sectional tensions that led to the Civil War.

- Civil War (1861–1865): The ultimate insurrection—the secession of eleven southern states—plunged the country into bloody conflict. The Union prevailed, at the cost of more than 600,000 lives.

- Haymarket Riot (1886): This Chicago labor protest turned deadly after a bomb killed police officers. The ensuing crackdown on labor movements exposed rifts in American industry and law enforcement.

Many of these historical insurrections involved open rebellion against the federal government, sometimes over economic hardship (as in Shays’ Rebellion or labor strikes) and at other times due to fundamental disputes over freedom and governance.

International Comparisons: Insurrections and Political Upheaval Elsewhere

Compared to American unrest, global history is replete with other attempted or successful insurrections:

- The Storming of the Bastille (France, 1789): A defining moment of the French Revolution, the people’s assault on the Bastille prison became symbolic of resistance to monarchy and autocracy.

- The Russian Revolution (1917): The Bolshevik insurrection toppled the provisional government, leading to a Communist regime that would dominate global affairs for decades.

- The German Beer Hall Putsch (1923): Adolf Hitler’s failed coup was crushed, but laid the groundwork for the eventual Nazi takeover.

- The attempted coup in Turkey (2016): A faction within the military tried to overthrow the government, resulting in hundreds of deaths and sweeping crackdowns afterward.

In each instance, insurrections targeted the core institutions of government, seeking immediate and often violent regime change. Many resulted in sweeping structural and policy changes—sometimes catastrophic, sometimes constructive.

What Makes January 6th Different?

Critics and historians agree that January 6 was unique in several ways. Unlike previous American insurrections, it:

- Specifically targeted the peaceful transfer of power. The certification of electoral votes has long symbolized American stability. To disrupt this process—a key pillar in the democratic process—marks a direct challenge to the core of republican governance.

- Was incited in real time by sitting officials. The involvement of elected leaders—and the sitting president—in encouraging the demonstration and subsequent riot set January 6 apart from earlier instances where uprisings typically came from outside or marginalized groups.

- Unfolded in the era of instant global communication. Social media fueled rapid organization, spread disinformation, and broadcast the event to millions instantly, undermining trust in institutions and raising the stakes for democratic stability.

- Occurred during a period of extreme polarization. While division is nothing new to America, recent years have seen declining faith in elections, judicial rulings, and the media—creating fertile ground for such an event.

Comparatively, while the Civil War was far deadlier and other insurrections led to considerable change, no other single event in the last 150 years struck at the ceremonial, process-oriented heart of U.S. democracy quite like January 6th.

Political and Trade Policy Consequences

In the aftermath of January 6, U.S. politics entered a new phase of combative rhetoric and deepened distrust. This polarization bleeds into areas essential to our website’s audience—namely, political stability’s impact on trade policy, tariffs, and international agreements.

- Global Perception: For decades, America stood as the reliable anchor for global trade deals, tariffs, and commerce. The January 6 attack shook allied confidence, raising fears about the predictability of U.S. commitments and the lawful enactment of trade policy.

- Legislative Paralysis: Partisan gridlock delayed or derailed consequential trade deals, tariff reforms, and stimulus packages. The attack escalated mistrust between parties, making coherent economic policy harder to achieve.

- Economic Uncertainty: Markets respond to perceived risk. Insurrection at the heart of U.S. government can prompt hesitancy from foreign investors, trade partners, and multinational corporations that rely on U.S. stability for their strategic planning.

The U.S. economy is tightly linked to its ability to maintain the rule of law and peaceful governance. Any insurrection, especially one of January 6’s magnitude, threatens that reputation.

Conclusion: A New Low—Or a Call to Action?

When placing January 6 in context alongside America’s—and the world’s—most notorious insurrections, its relative bloodlessness may seem less consequential than the Civil War or the French Revolution. Yet, in terms of symbolism and impact on democratic institutions, it hits uniquely hard. The targeting of the transfer of power—a globally admired tradition—signifies not just a national crisis, but a warning to democracies worldwide.

Is it a “new low”? In some respects, yes: No previous insurrection in American history has so directly aimed to reverse an election’s outcome within the halls of Congress. The rapid spread of disinformation through digital platforms and the encouragement by elements within the government heighten the sense of crisis.

Yet, history shows that crises can invite renewal. The immediate aftermath saw renewed debates on safeguarding democracy, regulating digital platforms, and shoring up institutional resilience. For those engaged in news, politics, or global trade, understanding these events is not just academic—it’s crucial for anticipating future risks and opportunities.

Vigilance, transparency, and civic education are the tools with which we can avoid repeating the darkest moments of our past. As we look forward, let’s hold leaders accountable, demand rigorous evidence in political discourse, and remember that the strength of democracy lies not in its immunity to crisis—but in its capacity to recover, reform, and persist.